Relevance Prediction from Eye-movements Using Semi-interpretable Convolutional Neural Networks

Relevance Prediction from Eye-movements Using Semi-interpretable Convolutional Neural Networks⌗

The primary purpose of Information Retrieval (IR) systems is to fetch content which is useful and relevant to people. IR systems have to cater to a variety of users, who may have wildly different mental models of what they consider to be useful and relevant.

Neuro-physiological methods, such as eye-tracking, provide an interesting avenue to observe users while they interact with information systems. Eye-tracking has been frequently used to assess if the screen-content is relevant to the user. Despite its many advantages such as being non-invasive and requiring very little effort, interpreting eye-tracking data is not straightforward.

For the dearth of standard methods, researchers resort to aggregating this data-stream into a set of single numbers, or features, at various levels of analysis (stimulus level, trial level, and/or participant level). By collapsing the eye-tracking data in this fashion, the fine grained information about the individual user’s progress is lost. This reduces the robustness and generalizability of insights gained from the analysis.

So, how do we preserve the details about the user’s progress and ensure more robustness and generalizability?

We propose an image-classification method to predict user’s perceived-relevance from their eye-movement patterns. Specifically, we convert participant’s eye-movement scanpaths into images, and then transform the relevance-prediction problem into an image-classification problem. For this purpose, we use state-of-the art image classifiers based on convolutional neural networks. Our method gives promising results, and outperforms many previously reported performances in similar studies by appreciable margins. We also attempt to interpret how the classifier possibly differentiates between user-reading-patterns on relevant and irrelevant documents.

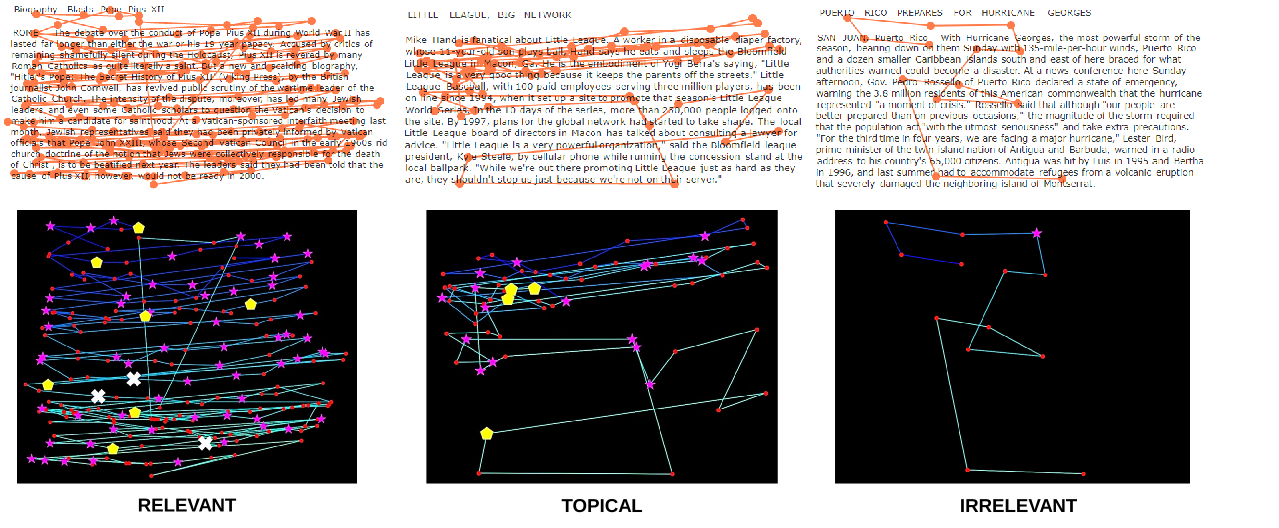

We generated scanpath images from eye-tracking data of user-document pairs, using only three attributes of eye-fixations: screen-coordinates (in pixels), fixation duration (in ms), and start time of the fixation relative to stimulus-onset.

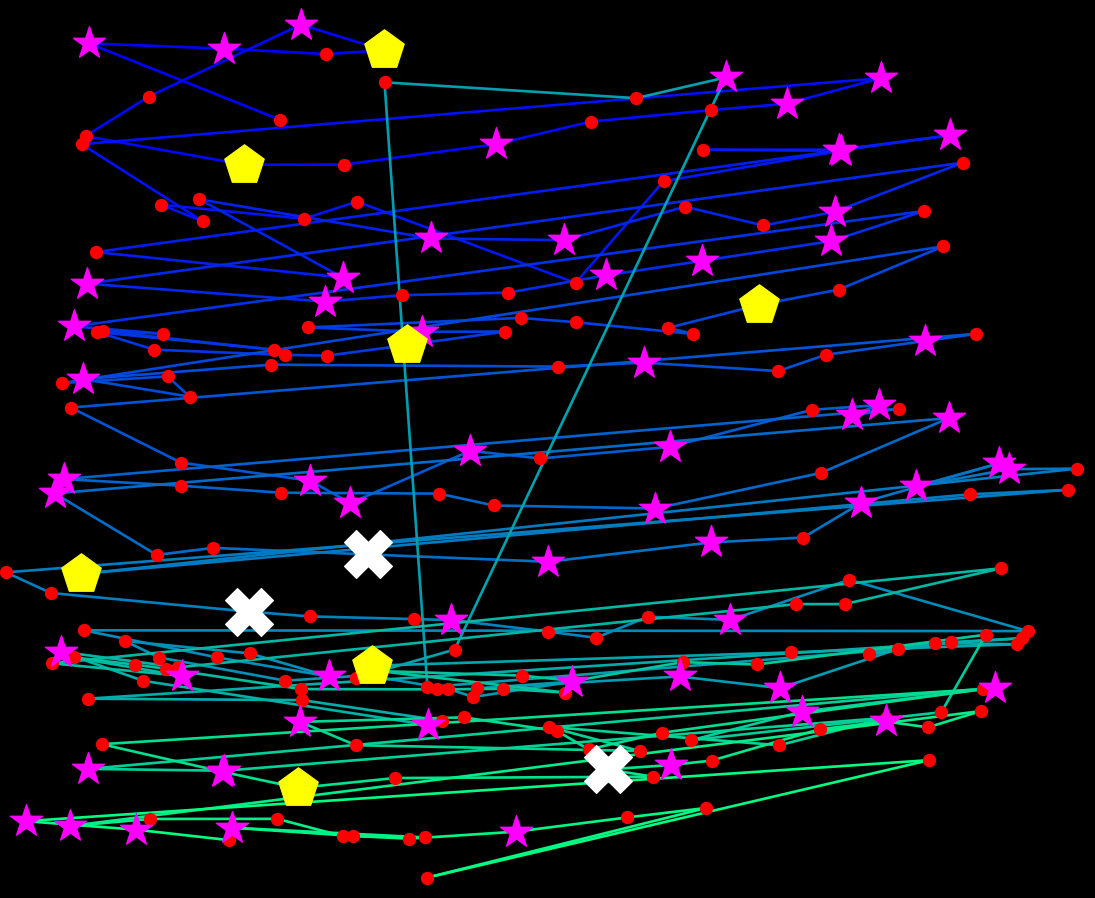

- Eye-fixations were encoded as marker points having varying shapes, sizes, and colours. The marker-size was made to increase with the increase in fixation duration. The fixation markers were chosen to be grossly different from each other (instead of, say, only circles), so that the CNN could possibly identify spatial patterns of similar-duration fixations.

- We plotted linearized saccades: the effective eye-movement between two fixations, represented as a straight line connecting the two points. We controlled the colour of the saccade lines to follow a linear colour scale, based on their temporal occurrence. The colour of the saccades changed linearly from blue (first saccade) to green (final saccade).

- Using a colour wheel, the colours of the different fixation markers were chosen to be far apart, from each other, as well as from the range of colours used to draw the saccades.

We hypothesized that these colour choices would enable the CNN classifier to easily distinguish between fixations and saccades, and identify necessary patterns. Examples of typical eye-movement patterns on three types of documents, and their corresponding generated scanpath images are shown in Figure 1. One such plot is shown in Figure 2.

Data was available for 24 participants, where each participant judged the binary relevance of 120 news articles. In total we had eye-tracking data for 2,880 user-document pairs, or 2,880 scanpaths.

We posed our binary classification problem as follows:

Given only the scanpath image of a user’s eye movements on a short news article, did the user perceive the article to be relevant for answering a trigger question?

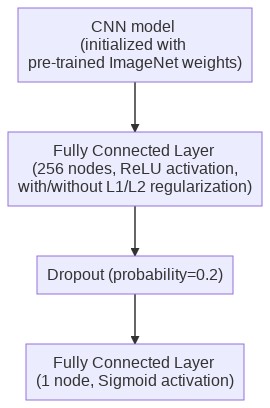

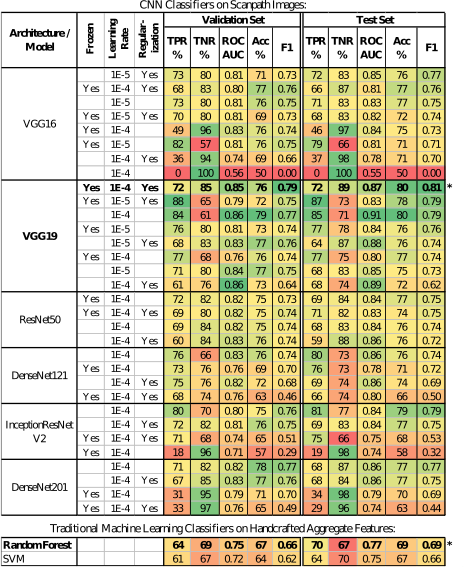

For this binary classification problem, we analysed the performance of six popular CNN based architectures: VGG16 and VGG19, DenseNet121 and DenseNet201, ResNet50 and InceptionResNet (version 2). The architecture was as below (Figure 3):

We trained the models on the training set, and used the validation set for very basic hyper-parameter tuning (learning rate, number of epochs, optimizer momentum, etc.). Since our intention was to see whether the method works, and not to obtain the best benchmark performance, we performed minimal hyper-parameter tuning. The top portion of the results table reports the results from the TensorFlow-Keras implementation.

We thank Splunk Inc. for the blog post on using mouse trajectories for fraud detection, which gave us the idea to adapt this approach for relevance prediction from eye-movements.